I. The Patent War: Selden, ALAM, and the Exhaustion Strategy

On October 22, 1903, a New York patent attorney named George Baldwin Selden did something that had never been done before: he sued a competitor for building automobiles. Selden had never manufactured a car. He had never sold one. He had, in the most literal sense, never driven one. What he possessed was something more valuable in Gilded Age America than any machine: a patent, U.S. Patent No. 549,160, filed in 1879 and finally issued in 1895, covering "the production and application of liquid hydrocarbon engines to road vehicles."[1]Selden's vision had crystallized seven years before he filed that patent. At the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, celebrating America's first century, he encountered George Brayton's massive internal combustion engine—a 1,600-pound contraption designed for stationary industrial use. Most visitors saw a curiosity. Selden, trained as both lawyer and engineer, saw something else entirely: a principle waiting to be miniaturized. By 1879, working in his Rochester workshop, he had reduced the Brayton design to 400 pounds. He filed his patent application on May 8, 1879. The witness who signed the document was a young bank clerk named George Eastman, who would later found Kodak. Selden never built a working automobile. He understood that controlling the principle would prove more valuable than building the machine.

The defendant was a forty-year-old Michigan machinist who had incorporated his third automobile company just four months earlier. Henry Ford was not the largest automaker in America. He was not the wealthiest. He was simply the one who refused to pay.

The Selden patent stands as one of the most instructive episodes in American industrial history, not because it reveals how patents protect innovation, but because it demonstrates how they can be weaponized to prevent it. Selden understood that a patent's value lies not in what it enables the holder to build, but in what it prevents others from building. He was, in the parlance of a later era, a troll.

The Selden patent is a fraud upon the public. It has been used as a club to frighten manufacturers out of the automobile business.

Henry Ford, 1903

Selden's genius was procedural. He filed his original application in 1879, then deployed a technique known as continuation practice to keep the application alive for sixteen years without ever allowing it to issue. Each time the Patent Office prepared to grant the patent, Selden filed amendments, additions, refinements. The statute at the time granted patents for seventeen years from the date of issuance, not the date of filing. Selden waited until 1895, when a commercial automobile industry was finally emerging, before allowing his patent to mature. He timed his harvest to coincide with someone else's planting.[2]

The result was a patent that covered virtually every gasoline-powered automobile, despite the fact that Selden had contributed nothing to the technology's development. Karl Benz had built the first true automobile in 1886. Gottlieb Daimler had done the same independently. Ransom Olds had begun mass production in 1901. None of them owed anything to George Selden's paper invention. All of them, theoretically, owed him royalties.

In 1903, the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers formed around the Selden patent. ALAM demanded 1.25 percent of every automobile's list price, collected from both manufacturers and their dealers. A five-member board controlled who could enter the industry. Frederic L. Smith of Olds Motor Works became president. The leading manufacturers of the era signed on: Packard, Cadillac, Peerless, Knox, Winton. The message to upstarts was clear: pay tribute or face litigation.[3]

The structural genius of ALAM lay in its origins. The association had begun as a defensive measure: manufacturers banding together to fight the Electric Vehicle Company's demand for a five percent royalty on the Selden patent. They had negotiated that number down to 1.25 percent. But then came the twist. Membership required unanimous approval by the five-member executive board. This gave existing members veto power over new entrants. An association designed to fight a patent monopoly had become a cartel controlling market entry. The same Frederic Smith who sat on ALAM's board had forced Ransom Olds out of Olds Motor Works the year before—for building cars too cheaply. ALAM wanted the luxury market. It did not want price competition.

Ford applied for a license in June 1903, weeks after incorporating his new company. ALAM rejected him. The association's stated reason was that Ford's operation was too small, too new, too likely to produce shoddy vehicles that would damage the industry's reputation. The actual reason was simpler: the established manufacturers saw no benefit in licensing a potential competitor. The cartel's purpose was exclusion, and Ford was excluded.

Ford's response demonstrated a strategic instinct that would define his career. Most manufacturers calculated the cost of litigation against the cost of the royalty, concluded the royalty was cheaper, and paid. Ford calculated something different. He calculated the publicity value of a man who tells an entire industry cartel to go to hell. ALAM began placing advertisements warning consumers that purchasing unlicensed automobiles would expose them to patent infringement liability. Ford countered with advertisements of his own, promising to defend every Ford purchaser against any legal action and posting a bond of $12 million to back the guarantee. The advertisements said nothing about the merits of the Selden patent. They said everything about the kind of man who built Ford automobiles.[4]

Ida Tarbell's exposé of Standard Oil had appeared just two years earlier. The Sherman Antitrust Act was being deployed against railroad combinations. A lone manufacturer fighting a trust composed of wealthy Eastern industrialists was a hero in the popular imagination. Ford understood this. He became that hero.

On September 15, 1909, after six years of litigation, Judge Charles Merrill Hough of the Southern District of New York ruled for ALAM. The Selden patent was valid, and Ford had infringed it. Ford's counsel had argued that the Selden engine was fundamentally different from any engine then in commercial use. Hough disagreed. The patent's claims were broad enough to cover the entire industry.[5]

Ford posted a $350,000 bond and appealed. Over the next sixteen months, his legal team, led by Ralzemond A. Parker and Edmund E. Wise, developed an argument that would prove decisive. The Selden patent specified a Brayton-cycle engine, a two-stroke design that had been obsolete since the 1880s. Every automobile manufacturer in America, including Ford, used an Otto-cycle engine, a four-stroke design that operated on fundamentally different principles. The patent, they argued, covered a technology that no one was actually using.[6]

On January 9, 1911, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed the lower court. Selden's patent was valid but economically worthless. It covered only Brayton-cycle engines, which no manufacturer had built in decades. The automobile industry was free.[7]

The gap between what Selden's patent claimed and what courts would enforce would repeat throughout the twentieth century. Selden believed he owned the automobile. The appeals court determined he owned a historical curiosity. The eight years of litigation cost both sides enormous sums, but Ford emerged with something priceless: a reputation as the man who had beaten the trust.

Consider the numbers: Between 1903 and 1911, while the patent litigation dragged on, Ford's production grew from 1,700 vehicles to 69,762 vehicles annually. His market share expanded from negligible to dominant. The Model T, introduced in 1908, became the best-selling automobile in America during the very years when ALAM claimed Ford had no right to build cars at all.[8]

Fifty manufacturers eventually paid the Selden royalty. The roster includes names that once commanded respect: Buick, Cadillac, Packard, Pierce-Arrow, Marmon, REO, Overland, Stearns, Mercer, Hudson. These companies followed the rules, however asinine those rules might have been. Ford broke them. Within two decades, most of the compliant manufacturers had disappeared or been absorbed. Ford remained.

The Selden episode established a template Ford would apply throughout his career. When facing legal or institutional opposition, he did not negotiate or capitulate. He fought publicly, casting himself as champion of the common man against entrenched interests. He converted litigation into marketing. And he assumed, correctly, that if he could survive long enough, circumstances would change in his favor.

After 1911, ALAM reorganized as the Automobile Board of Trade, later becoming the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce, then the Automobile Manufacturers Association. The organization that had tried to exclude Ford eventually honored him. The patent troll's weapon had been turned into scrap.

George Selden received approximately $200,000 in royalties before the court's decision ended his income stream. He died in 1922, largely forgotten. His contribution to the automobile industry was negative: years of litigation that enriched lawyers, intimidated innovators, and delayed progress. His patent is remembered today as a case study in how intellectual property can be perverted into a tool of obstruction.

Ford remembered Selden differently. The lesson he drew was not about patents or courts but about the nature of opposition. He had been told he could not build automobiles. He built them anyway. He had been told he would be sued into bankruptcy. He became one of the two richest men in America, second only to John D. Rockefeller. The experience taught him that established authorities were obstacles to be overcome, not guides to be followed. It was a lesson he applied, with diminishing success, for the rest of his life.

The Exhaustion Strategy

Ford's approach to the Selden litigation provides a template for asymmetric legal warfare: survive long enough to win, regardless of the formal outcome.

- Assess whether you can survive the litigation longer than your opponent can afford to pursue it. Time is a weapon.

- Convert defensive litigation into offensive marketing. Cast yourself as the underdog fighting an unjust system.

- Indemnify your customers against any legal consequence. Transfer their risk to yourself, earning their loyalty.

- Continue normal operations throughout. Never allow litigation to slow your commercial progress.

- Explore every technical and procedural defense. Victory may come from unexpected directions.

- Plan for multiple outcomes. Even a legal loss can be a commercial win if you have built enough momentum.

Works when your resources exceed your opponent's patience. When public sympathy favors the defendant. When continued operation builds strategic position regardless of verdict.

Adverse judgment with immediate enforcement. Injunctive relief that halts operations. Reputational damage if the public sides with plaintiffs. Catastrophic damages if the bet is wrong.

II. The Shareholder War: Dodge v. Ford and the Price of Control

"I will build a motor car for the great multitude." Ford made this declaration in 1907, and by 1916 he had fulfilled it beyond any reasonable expectation. The Model T dominated American roads. Ford's accountants had calculated a remarkable relationship: reducing the Model T's price by one dollar increased annual sales by 50,000 units. Ford wanted to push this logic to its limit—cut the price to $250 or less, reinvest every dollar of profit into capacity expansion, and put an automobile within reach of every American family. The Dodge brothers wanted those profits distributed to shareholders. On November 2, 1916, they filed suit, and the resulting decision would shape corporate law for a century.[9]The timing carried its own insult: the brothers filed the day after attending Edsel Ford's wedding to Eleanor Clay, where they had been guests.

The Dodge brothers were not ordinary plaintiffs. They had been present at Ford Motor Company's creation in 1903, receiving ten percent of the stock in exchange for supplying critical components: engines, transmissions, and axles. Their machine shop in Detroit had produced the mechanical heart of every early Ford automobile. If Ford Motor had failed, the Dodges had agreed to accept the entire company as payment. It did not fail, and by 1916 their stake was worth approximately $35 million.[10]

The brothers had left Ford's board in 1913 to launch their own automobile company. They needed capital. Ford dividends had been their primary source. By 1916, Ford Motor Company sat on accumulated profits exceeding $60 million, yet Henry Ford had announced he would pay no more special dividends. All surplus would be reinvested in expansion and price reductions.

Ford stated his position with characteristic bluntness: "My ambition is to employ still more men, to spread the benefits of this industrial system to the greatest possible number, to help them build up their lives and their homes. To do this we are putting the greatest share of our profits back in the business."[11]

The Dodges' complaint was procedurally simple. Ford Motor Company existed to generate returns for its shareholders. By refusing to distribute accumulated profits, the board was breaching its duty to the owners. The company's purpose was not philanthropy, employment, or social welfare. Its purpose was profit.

A business corporation is organized and carried on primarily for the profit of the stockholders. The powers of the directors are to be employed for that end.

Chief Justice Russell C. Ostrander, Michigan Supreme Court

Ford's actual motives were more complex than his public statements suggested. The Dodge brothers were using Ford dividends to build a competing automobile company. Every dollar Ford paid in dividends was a dollar that might fund a rival's factory. Withholding dividends was not philanthropy; it was competitive strategy disguised as social conscience.

The case proceeded through the Michigan courts with unusual speed. Trial testimony revealed the extraordinary profitability of Ford Motor Company. Between 1903 and 1916, the company had paid $41 million in special dividends on $2 million in capital. Regular dividends of five percent monthly, compounded across thirteen years, had returned more than sixty times the original investment. The Dodges were not impoverished shareholders seeking sustenance. They were millionaires demanding more millions.

In February 1919, the Michigan Supreme Court issued its ruling. Chief Justice Russell C. Ostrander wrote for the majority. The court affirmed that Ford Motor Company was obligated to consider shareholder interests paramount. It ordered the company to pay a special dividend of $19.3 million, plus interest. On the question of Ford's expansion plans, however, the court was more deferential, upholding the board's discretion to make reasonable business investments.[12]

The case is remembered today as the cornerstone of shareholder primacy doctrine. Generations of law students have studied Ostrander's opinion as establishing that corporations exist to maximize returns for owners. This interpretation has influenced everything from hostile takeover jurisprudence to executive compensation schemes. It has been cited to justify every variety of cost-cutting, from layoffs to environmental neglect.

The irony is that the conventional interpretation may be wrong. Legal scholars including Lynn Stout have argued that Dodge v. Ford actually stands for a narrower proposition: that directors cannot openly repudiate their obligation to shareholders while pursuing alternative goals. The business judgment rule, also affirmed in the case, grants directors substantial latitude to make decisions that do not directly maximize short-term profits. Ford lost not because he prioritized stakeholders over shareholders, but because he publicly announced he was doing so.[13]

Ford's response to the verdict demonstrated that he understood power better than law. He could not prevent the ordered dividend, but he could prevent future litigation by eliminating future plaintiffs. He announced in March 1919 that he was forming a new company to build automobiles even cheaper than the Model T. The Ford Motor Company could do whatever the minority shareholders wanted with their enterprise. He would simply compete against them.

The threat was credible. Ford at sixty-five had lost none of his competitive energy. A new Ford company would draw on his name, his dealers, his suppliers, his expertise. The existing Ford Motor Company would become a shell. The minority shareholders faced a choice: sell at a reasonable price or watch their investment become worthless.

Negotiations proceeded through intermediaries. Ford's agents, operating through a shell company called the Eastern Holding Company, contacted each minority shareholder individually. The Dodges sold for $25 million. James Couzens, who had run Ford's business operations for a decade before leaving in 1915, sold for $30 million. Horace Rackham and John Anderson, the lawyers who had helped organize the company in 1903, received $12.5 million each. The heirs of John Gray received $26.25 million. Even Rosetta Couzens Hauss, James Couzens' sister, who had invested exactly $100 in 1903, received $262,500.[14]

The total: $105,820,894 for 8,300 shares, representing 41.5 percent of the company. Ford financed the purchase by borrowing $75 million from a banking syndicate led by Chase Securities, the first time in his life he had borrowed money for any purpose. He had never taken a mortgage on his home. He had never carried personal debt. The experience reinforced his distrust of financial institutions, a distrust that would cost his company dearly during the Depression.

By July 1919, Henry Ford, his wife Clara, and their son Edsel owned 100 percent of Ford Motor Company. Henry held 55.19 percent, Clara 3.14 percent, and Edsel 41.67 percent. The company was reorganized under a Delaware charter, which offered more favorable corporate law. The Dodges were gone. Couzens was gone. The lawyers and investors who had shared in Ford's triumph were paid off and sent away. Ford Motor Company had become what Henry Ford had always wanted: a personal instrument, answerable to no one but himself.

Both Dodge brothers died within eleven months of receiving their buyout proceeds. John died of influenza in January 1920 at age fifty-five. Horace died of cirrhosis the following December at age fifty-two. Their automobile company, which they had built with Ford dividends, survived until 1928, when Walter Chrysler purchased it to create the third member of Detroit's Big Three.

The buyout enabled everything that followed at Ford Motor Company, both the triumphs and the catastrophes. Without minority shareholders, there was no one to question Henry Ford's decisions. No board could overrule him. No investor could demand accountability. The River Rouge plant, the most ambitious vertical integration project in industrial history, was built with money that might otherwise have gone to dividends. So was Fordlandia, the disastrous Brazilian rubber plantation. So was the Dearborn Independent, the newspaper that published anti-Semitic conspiracy theories for seven years.

The Dodge case established a precedent that founders have sought to circumvent ever since. Mark Zuckerberg structured Facebook with dual-class shares, ensuring that public shareholders could never outvote him regardless of their economic stake. Larry Page and Sergey Brin did the same at Google. The Dodge brothers' lawsuit taught a century of entrepreneurs that shared ownership means shared control, and shared control means vulnerability to those who do not share your vision.

Ford's solution was simpler and more expensive: he bought everyone out. The cost was nine figures. The benefit was absolute authority. Whether that authority was worth the price is a question that Ford Motor Company's subsequent history answers differently depending on the decade.

The Governance Unlock

Ford's response to shareholder opposition provides a template for founders seeking to eliminate governance constraints.

- Identify the true motivation of opposing shareholders. Are they seeking returns, or seeking to constrain your decisions?

- Create a credible alternative that makes their current position worthless. Ford's threat to start a competing company forced shareholders to negotiate.

- Negotiate individually, not collectively. Shareholders who cannot coordinate are easier to buy out.

- Use leverage strategically. Ford borrowed for the first time in his life because eliminating shareholders was worth the cost.

- Consolidate control completely. Partial buyouts leave residual opposition. Ford purchased every share he did not already own.

- Restructure governance to prevent recurrence. Delaware incorporation offered Ford more favorable law than Michigan.

Works when you have resources to purchase all opposition. When your competitive position makes alternative ventures credible. When shareholders are fragmented and cannot coordinate resistance.

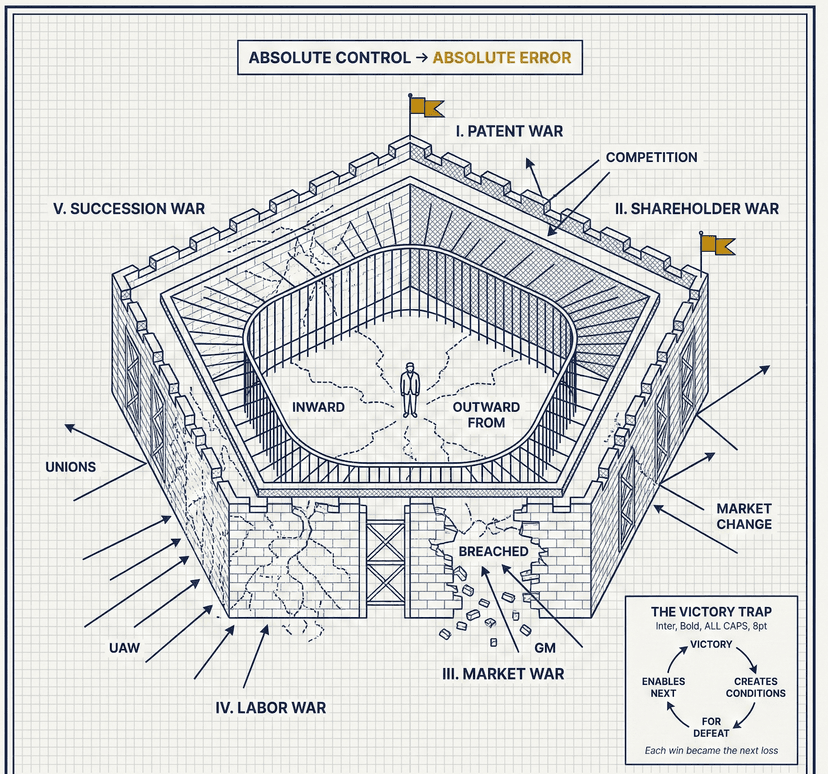

The cost may be higher than the benefit. Debt incurred for buyouts constrains future operations. Absolute control enables absolute errors. No one remains to tell the founder he is wrong.

III. The Market War: Sloan, Chevrolet, and the Obsolescence of Certainty

In 1921, Ford Motor Company controlled approximately sixty percent of the American automobile market. Chevrolet held four percent. Within six years, General Motors would overtake Ford, and Ford would never regain the lead. The reversal stands as one of the most consequential shifts in American industrial history, and its causes reveal everything about the difference between building a market and defending one.[15]The man who engineered GM's victory was not a manufacturer but an administrator. Alfred Pritchard Sloan Jr. had trained as an electrical engineer at MIT and made his first fortune in roller bearings. He had no particular feeling for automobiles. What he understood was organization, and in 1920, General Motors desperately needed to be organized.

William Crapo Durant, the company's founder, had assembled GM through a series of acquisitions so rapid that even he could not keep track of what he owned. Durant was a salesman of preternatural gifts; Walter Chrysler said he "could coax a bird right down out of a tree."[16] But Durant was also a gambler who believed that expansion solved every problem. By 1920, GM comprised Buick, Cadillac, Oldsmobile, Oakland (later Pontiac), Chevrolet, and dozens of parts suppliers, with no coordination between divisions and no coherent strategy for the whole.

Durant's second expulsion from GM, in November 1920, created the opening Sloan needed. The DuPont family, which had invested heavily in GM during World War I, installed Pierre du Pont as president. Du Pont had no interest in running an automobile company; he appointed Sloan to do it for him. Sloan's title was initially Executive Vice President of Operations. His actual role was to invent the modern corporation.

Sloan's first insight was that GM's chaos was also its opportunity. Ford offered one product: the Model T, available in one configuration, at one price point. GM could offer a ladder. "A car for every purse and purpose," Sloan called it. Chevrolet at the bottom for buyers stretching to afford their first automobile. Pontiac and Oldsmobile in the middle for the aspiring. Buick for the arrived. Cadillac for those who had no need to ask the price.[17]

The old master had failed to master change. He left behind a car that no longer offered the best buy, even as raw, basic transportation.

Alfred P. Sloan

The ladder required coordination that Durant had never achieved. Each division needed distinct positioning to avoid cannibalizing its siblings. Prices had to overlap slightly, so that a successful Chevrolet buyer's next car would be a Pontiac, not a Ford. Styling had to differentiate, so that neighbors could see which rung you occupied. Sloan imposed central financial controls while preserving divisional autonomy, a structure that business schools would later call the multidivisional form, or M-form. The M-form became the template for industrial organization throughout the twentieth century.

Sloan's second insight was that the automobile market had fundamentally changed. In 1908, when Ford introduced the Model T, most Americans had never owned a car. The market consisted of first-time buyers seeking basic transportation. Price was the dominant consideration. Reliability mattered. Style did not.

By 1920, the market was saturating. Millions of Americans already owned automobiles, many of them Model Ts. These buyers did not want basic transportation; they already had it. They wanted something better, something newer, something that would announce to their neighbors that they had prospered. Ford was still selling first cars to a market increasingly composed of second-car buyers.

The instrument of Sloan's strategy was a Hollywood custom-body designer named Harley Earl. In 1926, Earl was running a shop in Los Angeles that built custom automobiles for movie stars. Lawrence P. Fisher, head of Cadillac, invited him to Detroit to design a new companion car called the LaSalle. The result was the first mass-produced automobile styled by a professional designer.

In 1927, Sloan created the Art and Colour Section, the automobile industry's first in-house design studio, and installed Earl as its director. GM's engineers initially dismissed Earl's team as "pretty picture boys" working in "the beauty parlor."[18] They stopped laughing when the styled cars outsold the engineered ones.

Earl's assignment was to make last year's car obsolete. He introduced clay modeling, which allowed rapid iteration on body shapes. He developed the annual model change, which created a reason for buyers to replace functional automobiles. He designed the tailfin, inspired by the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter, and watched it become the defining visual element of 1950s America. The first tailfins appeared on the 1948 Cadillac. By 1959, they had grown to absurd proportions, peaking on the Cadillac El Dorado Biarritz, a chrome-encrusted monument to American postwar excess.[19]

Sloan and Earl called their strategy "Dynamic Obsolescence." Critics called it planned obsolescence. The principle was identical: make customers dissatisfied with what they owned. Ford had built cars to last. GM built cars to be replaced.

The financial innovation that enabled GM's strategy was equally important. In 1919, Sloan created the General Motors Acceptance Corporation, which allowed buyers to purchase automobiles on installment credit. Ford, who distrusted debt in all its forms, refused to offer financing until 1928. By then, two-thirds of all new car purchases in America were financed, and most of those loans came from GMAC.[20]

Ford's stubbornness on credit reflected a broader philosophy. He believed that debt was immoral, that consumers should save until they could pay cash, that installment purchases were a trap that impoverished working families. He was not entirely wrong. But his moral position did not change the fact that families wanted cars now, not after years of saving, and GM was happy to accommodate them.

The Model T's technological limitations compounded Ford's strategic errors. The car used a planetary transmission that required a learned technique to operate, while GM and other manufacturers had adopted the conventional sliding-gear transmission that remains standard today. The Model T offered only mechanical brakes, which Ford defended long after competitors had switched to hydraulics. The styling had not changed meaningfully since 1908. By the mid-1920s, used cars from other manufacturers were perceived as better values than new Model Ts.

Ford's defenders within the company could not persuade him to change course. In January 1926, Ernest Kanzler, Ford's son-in-law and a senior executive, wrote an eight-page memorandum urging modernization. The Model T was losing market share. Competitors offered features that customers wanted. Continued stubbornness would cost the company its dominant position. Ford read the memo and fired Kanzler.[21]

Edsel Ford, who nominally served as president of Ford Motor Company, shared Kanzler's views but lacked the authority to act on them. The pattern of their relationship was already established: Edsel would propose innovation, Henry would reject it, and Henry's will would prevail. When Edsel developed a prototype modern sedan with hydraulic brakes and conventional transmission, Henry reportedly took a sledgehammer to it.

The end came in May 1927. Ford Motor Company shut down for six months to retool for a new model. During this period, the company produced not a single automobile. Fifteen million Model Ts had been built. No more would follow. Ford announced the Model A (reusing the name from 1903) with features that Edsel had advocated for years: hydraulic brakes, sliding-gear transmission, multiple body styles, multiple colors.

The Model A was a commercial success. Ten million Americans visited Ford dealerships within 36 hours of its unveiling. 1.25 million people saw it at Madison Square Garden in five days. Within six months, Ford had sold two million units. But the Model A was not a leap ahead of GM; it was a catch-up. Ford had spent six months and untold millions to achieve parity with a competitor that had overtaken it two years earlier.[22]

Sloan's assessment was characteristically clinical: "The old master had failed to master change. He left behind a car that no longer offered the best buy, even as raw, basic transportation. Mr. Ford, who had had so many brilliant insights in earlier years, seemed never to understand how completely his market had changed."[23]

Durant, the man Sloan replaced, ended his career running a bowling alley in Flint, Michigan. He had lost two automobile empires and several personal fortunes. In his final years, he survived on a pension quietly arranged by Sloan, supplemented by handouts from the Chrysler family. Durant died in 1947, the same year as Henry Ford, but in circumstances that could not have been more different. Ford left an estate worth hundreds of millions. Durant left debts.

The contrast illuminates the difference between vision and execution. Durant saw that the automobile industry would consolidate around a few dominant manufacturers. He was right. He saw that those manufacturers would need to offer multiple brands at multiple price points. He was right. He saw that vertical integration would provide competitive advantage. He was right about everything except the one thing that mattered: he could not build an organization capable of executing his vision. Sloan could.

Ford's failure was different in kind. He had built the organization. He had dominated the market. He had the resources to respond to GM's challenge. What he lacked was the willingness to see that the world had changed. The Model T was perfect for 1908. By 1927, perfection was no longer the relevant criterion. Customers wanted progress, not perfection. Ford offered them archaeology.

The Certainty Trap (Anti-Playbook)

Ford's loss to GM demonstrates how the confidence that enables breakthrough prevents adaptation. This anti-playbook identifies warning signs that conviction has become liability.

- Monitor the gap between your assumptions and market reality. Ford assumed price was the dominant consideration; by 1925, style mattered more.

- Create protected spaces for dissent. Kanzler's memo should have prompted reconsideration, not termination.

- Distinguish between principles and preferences. Ford's commitment to simplicity was a principle; his refusal to offer colors was a preference defended as principle.

- Track competitor innovations you have dismissed. Each dismissal should be recorded and periodically reviewed.

- Empower successors to challenge assumptions. Edsel's views were correct; his authority to act on them was absent.

Recognition signals: Declining market share despite operational excellence. Customer complaints dismissed as ignorance. Talented subordinates departing or falling silent. Competitors adopting features you have rejected.

The Certainty Trap is insidious because certainty feels like strength. Ford's conviction had built the Model T; the same conviction prevented its replacement. What you cannot doubt, you cannot change.

IV. The Labor War: Bennett, the UAW, and the Violence of Paternalism

The man who would become Henry Ford's enforcer stood five feet six inches tall and weighed 145 pounds. Harry Herbert Bennett had served in the Navy, boxed professionally, and cultivated connections with Detroit's criminal underworld. Ford hired him in 1916 or 1917 as a watchman. By 1921, Bennett commanded the Service Department, Ford Motor Company's internal security force. By 1943, he was the second most powerful man in the company, answering only to Henry Ford himself.[24]Bennett's rise reflected Ford's evolving psychology. The man who had doubled wages in 1914 to reduce turnover had become, by the 1930s, someone who viewed his workers with suspicion and his critics with contempt. The Five Dollar Day had been paternalism at its most generous. The Service Department was paternalism at its most brutal. Both assumed that workers were children who needed guidance. The difference was whether that guidance came through wages or through fear.

The Service Department's official function was plant security. Its actual function was surveillance, intimidation, and the suppression of labor organizing. Bennett recruited from the ranks of ex-convicts, former athletes, and men comfortable with violence. At its peak, the department employed approximately 3,000 people, a private army operating within an industrial enterprise. Bennett himself kept a pistol in his desk and tigers in his yard.[25]

The first blood came on March 7, 1932, during what became known as the Ford Hunger March. The Communist Party had organized a demonstration of unemployed workers to march from Detroit to the River Rouge plant in Dearborn. Approximately 3,000 people participated. As the marchers approached the plant gate, Dearborn police and Ford security opened fire. Five men died. Dozens more were wounded. The dead were buried beneath a monument inscribed with a quotation from Lenin.[26]

The violence of 1932 was prelude. The main conflict came five years later, after the passage of the National Labor Relations Act, which guaranteed workers the right to organize and bargain collectively. General Motors recognized the United Automobile Workers in February 1937, following the sit-down strikes in Flint. Chrysler followed in April. Ford, alone among the major automakers, refused.

We'll never recognize the UAW, or any other union. Labor Unions are the worst thing that ever struck the earth.

Henry Ford, 1937

On May 26, 1937, UAW organizers Walter Reuther and Richard Frankensteen arrived at the Miller Road overpass outside the Rouge plant to distribute leaflets. They had notified the press. They expected confrontation and planned to document it. What they did not expect was the savagery of Bennett's response.

As Reuther and Frankensteen posed for photographs on the overpass, approximately forty men in civilian clothes surrounded them. The attackers, later identified as members of Bennett's Service Department, beat the union organizers systematically. Frankensteen's coat was pulled over his head to blind him while men kicked him in the kidneys. Reuther was thrown down a flight of metal stairs. Sixteen people were injured, including women who had been distributing leaflets.[27]

The attackers made one critical error: they failed to confiscate all the cameras. James Kilpatrick of the Detroit News escaped with his film. The photographs ran in newspapers across the country, showing well-dressed thugs beating unarmed men on a pedestrian bridge. The Battle of the Overpass, as it became known, transformed Ford from employer into villain in the public imagination.

Ford's public response was denial. The company claimed that the union organizers had attacked first, that Ford employees had merely defended themselves. Bennett told reporters that he had no idea who the attackers were. The denials were so transparent that they compounded the reputational damage. The National Labor Relations Board found Ford guilty of unfair labor practices on December 22, 1937, and ordered the company to cease interfering with union organizing.[28]

Ford ignored the order. For four more years, the company continued to fire union sympathizers, maintain surveillance on workers, and deploy Bennett's men against organizers. Ford was the last major automaker to recognize the UAW, and the recognition came only after one final confrontation made continued resistance impossible.

In April 1941, Ford fired eight union members at the Rouge plant. The UAW called a strike. Within hours, 50,000 workers had walked out. Picket lines surrounded the plant. African American workers, whom Ford had hired in larger numbers than any other automaker, initially remained inside, creating racial tensions that threatened to explode into violence.[29]

Ford's initial response was characteristic: he would shut down the company rather than submit. He had beaten the Selden patent. He had beaten the minority shareholders. He would beat the union. Charles Sorensen, Ford's production chief, later recalled that Ford was "very close to following through with a threat to break up the company rather than cooperate."[30]

Clara Ford changed his mind. His wife of fifty-three years had supported every venture, tolerated every eccentricity, and rarely interfered in company business. Clara told Henry that if he destroyed the family business, she would leave him. It was the only ultimatum of their marriage, and it worked.

On June 20, 1941, Ford Motor Company signed a contract with the UAW that was more generous than either GM's or Chrysler's. The company agreed to a union shop, meaning all workers would be required to join. It agreed to check-off, meaning dues would be deducted automatically from paychecks. It agreed to reinstate workers who had been fired for union activity and to pay back wages. The most stubborn holdout had become the most accommodating signatory.

Ford's explanation for the reversal was characteristically revisionist. About a year after signing the contract, he told Walter Reuther: "It was one of the most sensible things Harry Bennett ever did when he got the UAW into this plant." When Reuther asked what he meant, Ford replied: "Well, you've been fighting General Motors and the Wall Street crowd. Now you're in here, and we've given you a union shop and more than you got out of them. That puts you on our side, doesn't it? We can fight General Motors and Wall Street together."[31]

The statement reveals the structure of Ford's mind in his final years. He had not changed his views about unions, workers, or his own righteousness. He had simply incorporated the union into his existing framework of enemies and allies. The union was no longer an enemy because it was now a weapon against his real enemies: the bankers, the competitors, the establishment he had fought his entire career. Ford could not admit error. He could only redefine victory.

Bennett survived the union victory and continued to accumulate power as Ford's health declined. By 1943, when Edsel Ford died, Bennett was positioning himself to control the company after Henry's death. He had convinced the aging founder that Edsel's sons were unfit to lead, that only Bennett could protect the Ford legacy. The final confrontation would wait until 1945, when Clara Ford intervened again, this time to save the company from the man who had enforced her husband's will for three decades.

The labor war cost Ford more than money or market share. It cost him the moral authority that had been his greatest asset. The man who had doubled wages, shortened hours, and hired the disabled was revealed as an employer who would use violence to prevent workers from organizing.

"A great business is really too big to be human," Ford had written in 1922. He meant it as justification for systems that removed discretion from workers. He did not mean it as self-indictment. But Bennett's Service Department was the natural terminus of that logic: a system so perfectly inhuman that it could beat a man half to death without anyone in particular deciding to do so. The Five Dollar Day and the Battle of the Overpass were not contradictions. They were the same principle applied with different tools. Ford believed he knew what was best for his workers. The question was never whether he would impose that belief. The question was only whether the imposition would feel like generosity or violence.

The Paternalism Trap (Anti-Playbook)

Ford's labor relations demonstrate how generosity without accountability creates unsustainable dependencies. This anti-playbook identifies warning signs that benevolent leadership is becoming malevolent control.

- Watch for the conflation of loyalty with agreement. When dissent is treated as ingratitude, generosity has become a tool of control.

- Monitor the emergence of enforcement mechanisms. Security forces that protect property are different from security forces that suppress speech.

- Track the response to external standards. Resistance to labor laws, safety regulations, or transparency requirements often signals that internal practices cannot survive scrutiny.

- Observe succession dynamics. Leaders who undermine potential successors are often protecting practices that would not survive their departure.

- Listen to the language of betrayal. When employees seeking fair treatment are described as ungrateful, the relationship has inverted from service to extraction.

Recognition signals: Generous compensation paired with intense surveillance. High turnover despite above-market wages. Internal security functions that exceed any plausible threat. Leaders who cannot tolerate disagreement.

Employees in paternalist systems often become dependent on benefits that are not portable. Breaking free requires accepting short-term losses for long-term autonomy.

V. The Succession War: Edsel, Eleanor, and the Destruction of an Heir

Edsel Bryant Ford became president of Ford Motor Company on December 31, 1918, at the age of twenty-five. He held the title for twenty-four years, until his death on May 26, 1943. In all that time, he was never permitted to exercise the authority the title implied. His father, who had promoted him, systematically undermined him. What Henry Ford did to his son—the daily humiliations, the public reversals, the cultivation of rivals who held Edsel in open contempt—was made crueler by the fact that it was inflicted by a father who, in his own way, loved his son.[32]The relationship between Henry and Edsel Ford cannot be understood through the lens of ordinary family dynamics. Henry Ford was not merely a demanding father; he was a man who had built the most valuable manufacturing company in the world through sheer force of certainty. That certainty extended to everything: engineering, business strategy, social policy, and child-rearing. Edsel's tragedy was to be raised by a man who could not distinguish between guiding a child and controlling a subordinate.

Edsel was everything his father was not. He had been educated at private schools. He moved comfortably among Detroit's elite. He collected art, patronized the Detroit Institute of Arts, and built a home designed by Albert Kahn in Grosse Pointe Shores that remains one of the finest examples of Cotswold architecture in America. He dressed well, spoke softly, and avoided confrontation. Henry, who dressed plainly and thrived on conflict, interpreted his son's refinement as weakness.

He killed my husband. He will not kill my son.

Eleanor Clay Ford, on Harry Bennett, 1945

The professional humiliations were relentless. Edsel would make a decision; Henry would reverse it. Edsel would hire an executive; Henry would fire him. Edsel would approve a design; Henry would order it destroyed. The pattern was so consistent that Ford executives learned to check with the elder Ford before implementing anything the younger Ford had ordered. Edsel's authority existed on paper. Henry's authority existed in fact.

Harry Bennett became the instrument of Edsel's degradation. Bennett reported nominally to Edsel but actually to Henry, and he made no secret of his contempt for the president he ostensibly served. When Edsel attempted to discipline Bennett's men, Bennett went to Henry, and Henry supported Bennett. The message to the organization was unmistakable: the son could be defied with impunity.

Yet Edsel's accomplishments, achieved despite constant interference, were substantial. He created the Mercury division to fill the gap between Ford and Lincoln in GM's ladder-style market segmentation. He supervised the development of the Lincoln-Zephyr, which brought streamlined design to American luxury cars. He personally oversaw the creation of the Lincoln Continental, working with designer E.T. "Bob" Gregorie on a car that would later be selected for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Frank Lloyd Wright called it "the most beautiful car in the world."[33]

The Continental's development revealed what Edsel might have achieved with his father's support. In 1938, Edsel asked Gregorie to design a personal car for his Florida vacation, something distinctive and European in character. Gregorie produced a long, low convertible with clean lines and minimal ornamentation. Edsel was delighted. Demand from friends and acquaintances led to limited production: 404 units in 1940, 400 in 1941, then wartime suspension. Only 5,324 were ever built. Each was essentially handmade. The Continental remains one of the most collectible American automobiles, a testament to what Ford Motor Company could produce when Edsel's taste prevailed.[34]

Edsel also championed the Model A's development when his father finally accepted that the Model T had to be replaced. He pushed for hydraulic brakes, which Ford finally adopted in 1939, more than a decade after competitors. He advocated for the conventional transmission that replaced the Model T's planetary gearbox. In nearly every case, Edsel was right, and in nearly every case, he had to wait years for his father to accept what was obvious to the rest of the industry.

The stress of this position contributed to Edsel's death. He developed stomach ulcers, then stomach cancer. He underwent surgery in January 1942 but continued working. By early 1943, the cancer had spread. He died on May 26, 1943, at the age of forty-nine. His father, eighty years old and showing signs of dementia, announced that he would resume the presidency himself.[35]

Henry Ford's eulogy for his son was characteristically self-serving. He blamed Edsel's death on his drinking, his lifestyle, his inability to handle stress. He could not accept that the stress had been largely of Henry's creation, that a lifetime of humiliation and overruling had worn down a man who had wanted nothing more than to serve the company his father had built.

The war years that followed Edsel's death were disastrous for Ford Motor Company. Henry was nominally in charge but increasingly incapable of making decisions. Bennett filled the vacuum, advancing his allies and removing anyone who might challenge his authority. Charles Sorensen, who had been with Ford since 1905 and had supervised the construction of Highland Park and River Rouge, was forced out in 1944 after Henry grew jealous of press coverage praising Sorensen's war production achievements.[36]

The company was losing approximately $10 million per month by early 1945. The federal government, which depended on Ford for war production, considered nationalization. Discussions in Washington explored whether executive intervention might be necessary to keep the company functioning. Ford Motor Company, which had been the most valuable manufacturing enterprise in the world, was approaching collapse.

Edsel's widow, Eleanor Clay Ford, held more than forty percent of the company's stock, inherited from her husband. She had watched Bennett destroy her husband. She would not allow him to destroy her sons. In the summer of 1945, Eleanor and Clara Ford confronted Henry with an ultimatum: install Henry Ford II as president, or Eleanor would sell her shares to outside investors, ending Ford family control of the company.

The threat was credible. Eleanor had the shares. Outside buyers, including GM, would have been eager to acquire them. Henry, despite his declining faculties, understood that family control was the one thing he valued more than personal authority. On September 20, 1945, he summoned his grandson to Fair Lane and informed him of the decision. The next day, Henry Ford II, twenty-eight years old, became president of Ford Motor Company.[37]

Henry Ford II's first act was to fire Harry Bennett. Bennett claimed to have a document, signed by Henry Ford, naming him as the decision-maker for the Ford family's voting shares. The document, if it existed, was never produced. Bennett cleared out his office and left the Rouge plant for the last time. Within weeks, his allies throughout the company were dismissed. The Service Department was disbanded. Ford Motor Company began the long process of rebuilding from the wreckage that founder's stubbornness and Bennett's malevolence had created.

The succession war illuminates a pattern that recurs in family businesses across cultures and centuries. Founders who built enterprises through personal force often cannot accept that their successors might build through different methods. Henry Ford could not see that Edsel's refinement was an asset, not a liability, that the company needed someone who could work with designers and managers and financiers rather than dominating them. The qualities that made Edsel different from his father were precisely the qualities that might have saved the company from its later decline.

The cruelest irony came fifteen years after Edsel's death. In 1957, Ford Motor Company launched a new car division, positioned between Ford and Mercury, exactly as Edsel had long advocated. The company named it the Edsel, over Henry Ford II's objections. The car was a commercial disaster, launched during a recession, plagued by quality problems, and burdened with styling that consumers found bizarre. Production ceased in 1960 after approximately 118,000 units. The name that should have honored Edsel Ford instead became a synonym for failure.[38]

VI. The War Within: Decline, Rescue, and the Whiz Kids

On April 7, 1947, the Rouge River flooded its banks and cut electrical power to Fair Lane, the estate Henry Ford had built forty years earlier. That night, by the light of kerosene lamps and candles, Henry Ford died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of eighty-three. He had been born by candlelight in 1863. He died by candlelight in 1947. In between, he had transformed the world and been transformed by it, not always for the better.[39]The Ford Motor Company he left behind was a shambles. The financial situation was catastrophic: losses exceeding $10 million monthly, with accounting systems so primitive that no one could say precisely how much money was being lost or where. The manufacturing facilities, which had been the most advanced in the world in 1920, were now decades behind competitors. The management ranks had been gutted by Bennett's purges and the founder's paranoia. The company that had once built half the automobiles in America now struggled to build any that people wanted to buy.

Henry Ford II, known within the company as "the Deuce," faced a challenge that would have overwhelmed most executives twice his age. He had been released from Navy service in July 1943 to help manage the company during his father Edsel's final illness. He had received virtually no preparation for leadership; the assumption had always been that Edsel would guide him for decades. Instead, he inherited a crisis.[40]

The Deuce's first critical decision was to seek help from outside. Ford Motor Company had always been insular, suspicious of outsiders, contemptuous of professional management. Henry Ford II recognized that insularity had nearly destroyed the enterprise. In August 1946, he hired Ernest R. Breech, a senior executive from General Motors subsidiary Bendix Aviation, to serve as executive vice president. Breech brought GM methods to Ford: decentralization, professional management, financial controls, and a willingness to challenge the founder's assumptions.

The second critical decision arrived unsolicited. On October 19, 1945, a thirty-two-year-old Army Air Forces colonel named Charles "Tex" Thornton sent a telegram to Henry Ford II proposing that Ford hire his entire team of ten statistical control officers as a package. The officers had spent the war applying quantitative analysis to military logistics, tracking everything from bomber efficiency to supply chain optimization. They averaged twenty-nine years old. None had any experience in automobile manufacturing. Thornton believed that was an advantage.[41]

Henry Ford II met with Thornton and was impressed. At the end of the meeting, before the young officers had even left the room, Ford said: "I want to hire all of you. Just put your name down and how much money you want." The premiums were substantial: salaries ranging from $8,000 to $15,000 annually, far above industry norms for their age and experience, plus performance bonuses. Ford's desperation had overcome the company's traditional parsimony.[42]

I am green and searching for answers. This company needs professional management, and it doesn't have any.

Henry Ford II, 1946

The ten officers became known as the Whiz Kids, initially a term of derision. Older Ford executives resented their youth, their methods, and their incessant questions. The Whiz Kids wandered through plants with clipboards, asking questions that no one had asked before: What does this operation cost? How do you know? Where are the records? The questions revealed that Ford Motor Company, after forty years of operation, could not answer basic questions about its own finances.

The group's composition would prove remarkable. Robert S. McNamara, who would eventually become Ford's president and then Secretary of Defense under Kennedy and Johnson. Arjay Miller, who would also become Ford's president. J. Edward Lundy, who would serve as chief financial officer and remain with the company until 1979, becoming one of the most influential figures in its postwar history. Jack Reith, who would turn around Ford of France and return to head the Mercury division. Seven of the ten eventually reached senior management positions.[43]

Thornton himself lasted only two years. His personality clashed with Breech and the other GM imports who were reshaping Ford's management. He departed in 1948 for Hughes Aircraft and later built Litton Industries into one of the first modern conglomerates. His exit was the Whiz Kids' first lesson in corporate politics: being right is not sufficient; being right in the right way matters equally.

The Whiz Kids' most visible achievement was the 1949 Ford, the car that saved the company. Developed in nineteen months from concept to production, an almost impossibly compressed timeline, the 1949 Ford was the first genuinely new Ford design since before the war. It abandoned the prewar styling language entirely, offering clean, modern lines that signaled a break with the past. On introduction day, 100,000 orders were placed. By year's end, Ford had sold over a million units.[44]

The less visible but more consequential achievement was the reconstruction of Ford's management systems. The Whiz Kids instituted the first real internal audits in the company's history. They developed financial controls that could track costs by division, by product, by operation. They created planning processes that linked production to demand forecasting. They reorganized the company along approximately fifteen profit centers, each with professional and semi-autonomous management. The chaos of the founder's later years was replaced with the discipline of professional administration.

McNamara's trajectory illustrated both the virtues and the limitations of the Whiz Kids' approach. He had earned an MBA from Harvard in 1939, taught there briefly, then spent the war applying statistical methods to bomber operations under Curtis LeMay. His analysis showed that approximately twenty percent of Eighth Air Force bombing missions were aborted, largely due to crew fear rather than mechanical failure. He helped devise scheduling systems that doubled the efficiency of B-29 transports. His analysis of jet stream patterns influenced LeMay's decision to conduct low-altitude firebombing raids against Japan.[45]

At Ford, McNamara rose rapidly: controller by 1948, vice president and general manager of Ford Division by 1955, group vice president responsible for all car and truck divisions by 1957. On November 9, 1960, he was named president of Ford Motor Company, the first person outside the Ford family to hold that title since the founder's departure in 1919. He held the position for five weeks before accepting appointment as Secretary of Defense.

The Whiz Kids' legacy at Ford was thus a paradox. They saved the company from collapse. They professionalized its management. They restored its competitiveness. But they also embedded a way of thinking that would eventually contribute to Detroit's decline. The Whiz Kids believed that what could be measured could be managed, and what could not be measured did not matter. They applied this principle with extraordinary success in the chaotic Ford of 1946. They applied it with less success to the Vietnam War. They bequeathed it to an American automobile industry that would spend the next four decades losing ground to Japanese competitors who thought differently about measurement, quality, and the role of workers in production.

Ford Motor Company became a publicly traded corporation on January 17, 1956, ending fifty-three years of family ownership. The initial public offering was the largest in American history to that point. The Ford Foundation, which Henry Ford had created primarily for tax reasons, sold shares to the public while the Ford family retained voting control through a dual-class structure. The founder's distrust of Wall Street survived his death, embedded in a governance arrangement that kept bankers and outside shareholders at arm's length.

Henry Ford II led the company until 1979, a tenure of thirty-four years that spanned the postwar boom, the rise of imports, the oil crises, and the beginning of Detroit's long decline. He was a more capable executive than his father had allowed his father to become, but he was also a Ford, with the family's characteristic certainty and impatience with dissent. He fired Lee Iacocca in 1978 with the explanation: "I just don't like you." Iacocca went to Chrysler and saved it. The Deuce's instincts were not always reliable.

The company Henry Ford built survived his worst decisions because it was large enough to absorb them and because his successors were capable of learning from his mistakes. The Model T's obsolescence was overcome by the Model A and the V-8. The labor wars were resolved by unionization. The management vacuum of the 1940s was filled by professionals from outside the family. The founder's antisemitism was quietly buried. Ford Motor Company in the twenty-first century bears little resemblance to the enterprise Henry Ford created, and that may be the most important measure of its success.

Henry Ford's wars were with everyone: patent holders, shareholders, competitors, workers, his own son, and ultimately with time itself. He won more than he lost, but the victories had costs. The Selden victory established his reputation but encouraged a contempt for legal constraints. The shareholder victory gave him control but removed anyone who might restrain him. The market war he lost because he could not see that the world had changed. The labor war he won only when his wife intervened. The succession war he won completely, destroying his son and nearly destroying his company. The war within he lost when his mind failed and his creation fell into the hands of a former boxer with criminal connections.

The candles that lit his deathbed in 1947 cast shadows that reached forward across decades. Ford Motor Company survived because it was too valuable to fail and because, in the end, the Ford family chose continuity over pride. The Whiz Kids and their methods, the public offering and its capital, the professional managers and their disciplines, all represented repudiations of the founder's philosophy. Henry Ford built something that could survive him. He did not build something that could remain as he had made it. Perhaps that is the most any founder can achieve.

The Turnaround Protocol

Henry Ford II's rescue of Ford Motor Company provides a template for inheritors facing organizational collapse.

- Acknowledge what you do not know. Ford II said plainly: 'I am green and searching for answers.' Pretending competence you lack delays the help you need.

- Import expertise aggressively. Breech from GM, the Whiz Kids from the military: Ford II recruited from wherever talent existed, ignoring institutional prejudices.

- Remove the previous regime's enforcers immediately. Bennett was fired on Ford II's first day. His allies followed within weeks. Speed matters; delay allows entrenchment.

- Establish measurement before strategy. The Whiz Kids' first task was discovering what Ford actually spent. You cannot fix what you cannot see.

- Create a visible victory quickly. The 1949 Ford, developed in nineteen months, proved that change was possible. Early wins build momentum and credibility.

- Institutionalize the changes through structure. Profit centers, financial controls, professional management: Ford II made the changes permanent through organizational design.

Works when the inheritor has legitimacy that outsiders lack. When crisis creates openness to change. When talented outsiders are available and willing. When resources exist to survive the transition period.

Imported methods may not suit the organization's context. Professional management may sacrifice distinctive advantages. Measurement culture may neglect unmeasurable values. The founder's errors may be overcorrected into opposite errors.

VII. Portable Playbooks: Ford's Wars Made Applicable

The wars Henry Ford fought, won, and lost reveal patterns that recur across industries, eras, and scales. Founders facing patent trolls, activist shareholders, market disruption, labor conflict, or succession crises will find Ford's experiences instructive, not as templates to copy but as case studies to analyze. The playbooks extracted from these conflicts are tools for thinking, not formulas for action. Each requires adaptation to specific circumstances. Each carries risks that Ford himself sometimes failed to anticipate.The Exhaustion Strategy teaches that litigation can be won through endurance rather than verdict. The Governance Unlock demonstrates that shareholder opposition can be eliminated through buyout, but absolute control enables absolute error. The Paternalism Trap warns that generosity without accountability becomes tyranny with better marketing. The Turnaround Protocol shows how inherited organizations can be rescued through imported expertise, rapid measurement, and visible early victories.

What unites these playbooks is a recognition that conflict is structural, not personal. Ford did not fight the Selden patent because George Selden was a bad man; he fought it because the patent system created incentives for obstruction. He did not fight the Dodges because they were ungrateful; he fought them because shareholder rights conflicted with founder control. He did not resist unionization because workers were enemies; he resisted it because collective bargaining threatened his vision of paternal authority. Understanding the structure of conflict, rather than the personalities involved, is the first step toward managing it effectively.

Ford's greatest strategic error was assuming that winning one war prepared him for the next. The methods that defeated Selden failed against Sloan. The certainty that built the Model T prevented the Model T's replacement. The authority that eliminated shareholders enabled the mistakes that nearly destroyed the company. Each victory created conditions for the next defeat. He never learned that the skills which create success and the skills which sustain it are not always the same skills.