The Paradox of Perfect Focus

Henry Ford died by candlelight. On April 7, 1947, a spring flood knocked out electricity to Fair Lane, his Dearborn estate. The man who had brought power to millions lay in a room lit by flame, surrounded by servants holding candles, as if the twentieth century had briefly reversed itself. He had visited Greenfield Village that afternoon, the museum he built to preserve the pre-industrial past he had done more than anyone to destroy.The irony would have been lost on Ford. He never grasped irony. His mind worked mechanically, proceeding from premises to conclusions with the relentless logic of an assembly line. When this logic was aimed at manufacturing, it produced results that changed civilization. When aimed at politics, society, or human psychology, it produced disasters that stained his legacy and revealed the limits of engineering as a philosophy of life.

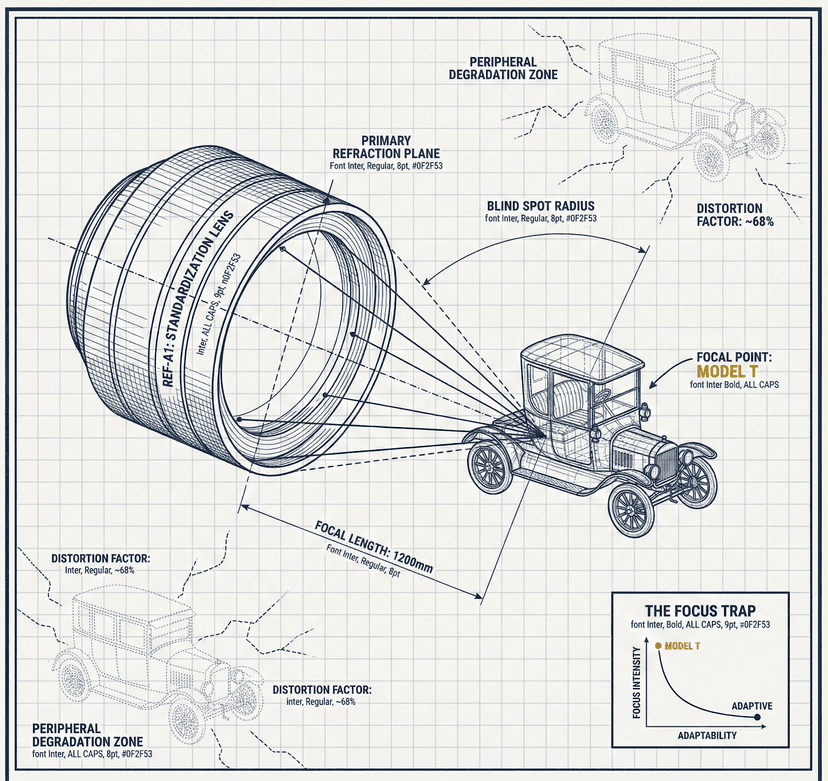

The central question of Ford's career is not how he succeeded. That part is well documented: standardization, the moving assembly line, the five-dollar day, vertical integration reaching from iron mines to dealer showrooms. The question is why the same mind that revolutionized manufacturing also published anti-Semitic propaganda that Hitler praised, resisted unionization with violence, built a disastrous rubber plantation in the Amazon, and nearly destroyed his own company by refusing to abandon a car that the market no longer wanted. Ford's triumphs and failures did not come from different traits. They came from the same trait applied to different domains. Focus enabled breakthrough and prevented adaptation. The mechanic's certainty that allowed Ford to ignore critics when they were wrong made him deaf to warnings when they were right.

Every founder's greatest strength creates their characteristic weakness. The same clarity that lets them see what others miss prevents them from seeing what they themselves miss.

Through-Line Insight

This pattern makes Ford worth studying. Every founder's greatest strength creates their characteristic weakness. The same clarity that lets them see what others miss prevents them from seeing what they themselves miss. Ford's story illuminates this dynamic with unusual clarity because his successes were so spectacular and his failures so complete.

Dearborn: The Farm Democracy and the Compulsion

Ford was a builder, and builders have a characteristic blindness. They see what doesn't exist and will it into being. They cannot see what does exist and imagine it transformed. Ford could envision a factory where none stood, a supply chain stretching from Minnesota iron mines to Brazilian rubber plantations, an automobile in every American driveway when horses still dominated the roads. But he could not envision his own factory evolved, his own car replaced, his own methods superseded. Builders make. They rarely remake. The same certainty that lets them create from nothing prevents them from revising what they've created. Ford embodied this pattern completely, and his story traces its arc from advantage to disaster.But the farm also revealed something else about Ford: a compulsion that governed his choices before he understood where it would lead. By age seven, he was repairing watches for neighbors. By twelve, he had built his own forge. At thirteen, he walked eight miles on dirt roads to retrieve a broken tool for his watch repair business rather than ask his father for money to replace it. He could have replaced it easily. His father would have given him the coins. The walk made no practical sense.

Great founders do not decide to be obsessive. They discover that they already are.

Pattern Recognition

Great founders do not decide to be obsessive. They discover that they already are. Ford's eight-mile walk revealed something about him that sacrifice and dedication cannot explain. The impulse to repair rather than replace was already compulsive, already governing his choices before he understood where it would lead. The same certainty that made him walk rather than ask would make him refuse to abandon the Model T when everyone around him could see it was failing, and would make him build a doomed rubber plantation in Brazil rather than accept dependence on outside suppliers. The trait was visible at thirteen. It would shape everything that followed.

Money as Transmitter: The Philosophy

Ford's philosophy of business was fully formed before his commercial success validated it. The temptation to reconstruct early thinking in light of later triumph must have been considerable. Yet the ideas Ford expressed to Lane in 1917, when she wrote his biography, match the ideas he would elaborate in his own books in 1922 and 1926. The consistency suggests genuine intellectual architecture rather than retrospective justification.The foundation was a particular understanding of money. "He regards money as an incident in his career," Lane wrote, "a sort of fuel to be poured in unlimited quantities into the tank of a great machine, a transmitter of energy that would otherwise die." The metaphor is electrical: money converts potential energy into kinetic energy. Hoarded money is wasted energy. The purpose of wealth is to keep it moving.

Money doesn't do me any good. I can't spend it on myself. Money has no value, anyway. It is merely a transmitter, like electricity.

Henry Ford

Ford articulated this directly: "Money doesn't do me any good. I can't spend it on myself. Money has no value, anyway. It is merely a transmitter, like electricity. I try to keep it moving as fast as I can, for the best interests of everybody concerned." His mentor Thomas Edison would have recognized the frame instantly. Edison spent decades fighting the "battle of currents," insisting that direct current was superior to alternating current. Edison was wrong about that particular electrical question. But the underlying intuition that energy systems require flow, that potential without kinetic is waste, shaped how Ford thought about capital decades before John Maynard Keynes formalized similar ideas about velocity of circulation.

Sam Walton drove a pickup truck despite being America's richest man. Warren Buffett still lives in the Omaha house he bought in 1958. Sam Zell described wealth as "a great way to keep score but not the object of the game." The pattern recurs among builders who accumulate fortunes while genuinely not caring about the fortune. Employees and investors can smell pretense. Ford's indifference to personal wealth was authentic, and the authenticity created trust.

Ford paired his theory of money with what might be called a democratic theory of value. The automobiles of the early 1900s were luxury items, built for wealthy enthusiasts who wanted prestige. Ford looked at this market and saw error. "The automobile of those days was like a steam yacht," he told Lane. "It was built for only a few people. Now anything that is good for only a few people is really no good. It's got to be good for everybody or in the end it will not survive."

The claim is remarkable for its confidence. Ford was not simply predicting that mass-market automobiles would be more profitable. He was claiming that goods serving only elites were fundamentally worthless, that the measure of value was breadth of access rather than exclusivity. Hans Wilsdorf, founding Rolex three years before Ford introduced the Model T, reached the opposite conclusion and built one of the most valuable luxury brands in history. Both were right about their markets. The split between Ford's democratization and Wilsdorf's exclusivity would define entire industries. Apple under Steve Jobs navigated both strategies, democratizing personal computing while maintaining premium pricing. The tension between mass access and exclusive quality is never fully resolved.

The 999 and the Lunch Wagon: Proving Ground and First Capital

Between the midnight test drive of 1896 and the founding of Ford Motor Company in 1903, Ford navigated a series of decisions that would determine whether his vision could become reality. The path was neither straight nor obvious. He failed twice before succeeding. He walked away from investors who wanted different products. He bet everything on a racing strategy that could have destroyed his reputation.The first test came in 1899, when a group of Detroit businessmen offered to finance an automobile company with Ford as chief engineer. Ford accepted, but the partnership soured quickly. The investors wanted to build expensive cars for wealthy buyers. Ford wanted cheap cars for ordinary people. The conflict was fundamental. Ford walked away rather than compromise.

The decision was principled but potentially ruinous. Ford was thirty-six, had spent his prime working years on automobiles, and had just rejected his only serious financing. His prospects looked grim. But Ford had noticed something about investors: they responded to spectacle more than argument. They needed, as Lane put it, "letters a mile high." The solution was racing.

Ford built a racing car and named it the "999" after the Empire State Express locomotive No. 999, which on May 10, 1893, became the first vehicle in history to officially exceed 100 miles per hour. The locomotive had reached 112.5 mph near Batavia, New York, based on milepost timings by reporters aboard. Anyone in 1902 understood the reference immediately. Ford was staking a claim, connecting his untested automobile to the most celebrated technological achievement of the previous generation.

But Ford's breakthrough required something he could not provide himself: capital. Here the story takes an unexpected turn. Ford's savior was not a banker but Coffee Jim, the lunch wagon owner who had become Ford's friend during years of late-night conversation over coffee and sandwiches. Jim had saved money from his modest business. More importantly, he believed in Ford personally.

See here, Ford, I'll take a chance. I'll back you. You go on, quit your job, build that car and race her. I'll put up the money.

Coffee Jim

"See here, Ford, I'll take a chance," Coffee Jim told him. "I'll back you. You go on, quit your job, build that car and race her. I'll put up the money." When Ford offered collateral, Coffee Jim refused. "Your word's all I want." Lane called the relationship "one of those accidental friendships which have great consequences."

Coffee Jim represents something older than venture capital: relationship capital, trust accumulated through repeated interaction, money given because of who someone is rather than what their spreadsheet shows. Ford's democratic instincts had practical consequences. The fancy investors came later. The lunch wagon proprietor came first.

With Coffee Jim's backing, Ford built the 999. The machine was a monster: essentially a bare engine mounted on wheels with a seat attached. No suspension. No differential. No protection for the driver. Professional racing drivers looked at it and refused. Ford's partner Tom Cooper knew a bicycle racer named Barney Oldfield who had never driven an automobile but possessed a useful characteristic: he did not understand the danger well enough to refuse.

Oldfield won the October 1902 race against Alexander Winton's machine by half a mile. Modern Formula One races are won by fractions of a second. A margin of half a mile is not a victory. It is a demonstration so overwhelming that argument becomes impossible. Within months, Ford had backing to start Ford Motor Company.

The racing gambit would echo through Ford's corporate DNA for decades. In 1963, Enzo Ferrari walked away from selling his company to Ford, publicly embarrassing Henry Ford II. Ford Motor Company spent $25 million to build the GT40 racing car with a single purpose: defeat Ferrari at Le Mans. The GT40's 1966 victory saw Ford take first, second, and third place. Racing creates credibility that advertising cannot buy.

Elon Musk grasped the same principle. When Tesla was a startup with no credibility, Musk built the Roadster. When SpaceX was nearly bankrupt after three failed Falcon 1 launches, the fourth launch transformed perception overnight. Binary public success beats years of quiet competence when your product is unproven and your reputation is nothing.

Clara's Seven Years: The Infrastructure of Genius

Behind Ford's success stood relationships that his biographers have systematically minimized. The most important was Clara Bryant, whom Ford married in 1888.Clara endured seven years of sacrifice while her husband built his first automobile. The couple lived in cramped rental housing on Ford's salary from the Edison Illuminating Company, roughly $40 to $45 per month. Money was perpetually short. Ford spent every spare hour and every spare dollar on his experiments. Clara managed the household on whatever remained.

On the night of June 4, 1896, Ford pushed his completed quadricycle through a doorway he had to widen with an axe because he had built the machine without measuring the exit. Clara followed on a bicycle, holding an umbrella over the exposed engine as Ford sputtered through rain-slicked streets. When Ford returned to Bagley Avenue at dawn, Clara was waiting with tears streaming down her face. Not upset. Proud.

Seven years. Seven years. Henry, at last you've done it.

Clara Bryant Ford

The pattern recurs across the history of innovation. Steve Jobs had Laurene, whose memorial speech described years of navigating a husband who could be "not my best self." Jeff Bezos built Amazon while his wife MacKenzie managed their household and drove him to work so he could write business plans in the passenger seat. Behind nearly every founder obsessed enough to change an industry stands a partner absorbing the cost of that obsession.

Edison did not finance Ford's first automobile. Clara's household economy did.

The Five-Dollar Day: When Arithmetic Revealed What Compassion Missed

On January 5, 1914, Ford announced that the minimum wage at Ford Motor Company would immediately rise to $5 per day, more than double the prevailing rate of $2.34 for unskilled factory labor. The Wall Street Journal called the policy "an economic crime." The New York Times reported that Ford's competitors considered him insane.Ford's factories hemorrhaged workers. At 370% annual turnover, he had to hire 52,000 people each year to maintain a workforce of 14,000. The $5 Day dropped turnover to 16%. Overnight, Ford went from the worst retention in the industry to the best by a factor of six.

The payment of five dollars a day for an eight-hour day was one of the finest cost-cutting moves we ever made.

Henry Ford, My Life and Work

The insight is not about generosity. It is about hidden costs. Most businesses optimize for visible costs. Ford optimized for total costs, including training, recruiting, quality variance, and productivity during the learning curve. His competitors thought he was paying more. He was actually paying less, once you counted everything.

The Shareholder Problem: Dodge v. Ford and the Buyout

The philosophy of service before profit sounds admirable in a memoir. In a courtroom, it sounds like grounds for a lawsuit. John and Horace Dodge filed suit demanding dividends. The Michigan Supreme Court established shareholder primacy: "A business corporation is organized and carried on primarily for the profit of the stockholders."Ford's response was characteristic. He bought everyone out. For $106 million, roughly $1.8 billion today, Ford and his son Edsel owned 100 percent of Ford Motor Company. The buyout enabled everything radical that followed.

Mark Zuckerberg solved the same problem differently with supervoting shares. The pattern recurs: visionary founders and public shareholders have structural conflicts.

River Rouge and Fordlandia: The Limits of Vertical Integration

The River Rouge complex embodied Ford's philosophy. Raw materials entered at one end; finished automobiles emerged at the other. Over 100,000 workers, 2,000 acres, 93 buildings. Ford claimed his company could take iron ore from a mine and deliver a finished automobile in eighty-one hours.But the same philosophy produced Fordlandia, his catastrophic Brazilian rubber plantation. Ford never consulted a botanist. He never visited Brazil. He imposed Dearborn on the jungle: American bungalows, American food, square dancing for recreation. Workers rioted. By 1945, Ford had spent $20 million and produced not a single pound of usable rubber.

Fordlandia isn't just the story of a plantation; it's a story about Ford's ego.

Greg Grandin

The Assembly Line: Mass Production and Its Consequences

On April 1, 1913, Ford's engineers tried an experiment at Highland Park. Assembly time for a magneto flywheel dropped from twenty minutes to five. Within a year, complete car assembly dropped from over twelve hours to ninety-three minutes.The Model T's price fell from $850 in 1908 to $260 by 1925. A Ford worker could buy a car with ten weeks of wages. By 1927, Ford had built 15 million Model Ts.

I never did a day's work in my life. It was all fun.

Henry Ford

The work that exhausted his employees energized him. This asymmetry is the key to everything: his genius, his blindness, his inability to understand why anyone would need a union. Taiichi Ohno at Toyota called Ford his primary teacher but improved precisely where Ford failed: continuous improvement, distributed authority, workers as sources of ideas. The student surpassed the teacher.

The Dearborn Independent: When Mechanical Thinking Met Human Complexity

In 1920, Ford launched the Dearborn Independent with "The International Jew," ninety-one weekly articles drawing on the forged "Protocols of the Elders of Zion." Circulation reached 700,000. Adolf Hitler praised Ford in Mein Kampf, kept his portrait in Munich, and in 1938 awarded Ford the Grand Cross of the German Eagle.The mechanical mind that solved production problems by identifying bottlenecks tried to solve social problems the same way. Ford's epistemology was mechanical: problems have identifiable causes, causes can be isolated, isolated causes can be eliminated. Applied to society, it produced conspiracy theories.

The Decline: When Focus Became Rigidity

Ford's story after 1920 is gradual decline masked by continued scale. Alfred P. Sloan at GM developed annual model changes and market segmentation. Sloan understood what Ford did not: once everyone had a car, they would want a different car, a better car.Ford's response was denial. "Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black." GM passed Ford in market share by 1930.

His son Edsel represented modern management. Henry systematically undermined him, overruling decisions, humiliating him in front of employees. Edsel died at forty-nine in 1943; contemporaries believed stress contributed. Harry Bennett, a former boxer with organized crime connections, rose to power. Ford was the last major automaker to accept unionization.

The Through-Line: What Ford's Life Illuminates

Henry Ford presents a problem for anyone seeking heroes or villains. He was both. The same person doubled wages and published propaganda that Hitler praised. The same certainty that enabled breakthrough prevented adaptation.Focus enables breakthrough and prevents adaptation. The same certainty that allows founders to ignore critics when they are wrong makes them deaf to warnings when they are right. The traits that produce success and failure are not different traits operating at different times. They are the same traits, operating in different circumstances.

The candles flickering in his bedroom on the night of his death cast shadows on a career that transformed the world and revealed the limits of transformation. Ford could read machinery. He never learned to read people with the same clarity. That was both his gift and his limitation.

Portable Playbooks

These frameworks are extracted from Ford's methods for conscious application.The Price-First Protocol

- Set the target price first, lower than you can currently deliver

- Work backward: what must be true operationally?

- Cut features before cutting corners

- Let price discipline substitute for management

Works when unit economics improve dramatically with scale

Can become excuse to ship inferior products

The Spectacle Demonstration Protocol

- Identify the single metric skeptics care about

- Engineer a public demonstration where victory is unambiguous

- Make the margin overwhelming, not incremental

- Convert attention into capital immediately

Works when you have genuine advantage that's hard to communicate

Spectacle that fails destroys credibility it was meant to build

The Turnover Calculus

- Calculate true cost of losing people: recruiting, training, quality

- Compare to cost of keeping them: above-market wages, benefits

- If retention costs less than replacement, pay for retention

- Accept that competitors will call you foolish

Works when jobs require skills that take time to develop

Can create entitlement without high performance standards