I. The Moving Line

On April 1, 1913, a foreman named Charles E. Sorensen arranged twenty-nine men along a waist-high row of magneto flywheels at the Highland Park plant in Detroit. Each man had been trained to perform a single operation: attaching a magnet, winding a coil, tightening a bolt. A chain dragged the flywheels past them at a fixed pace. Sorensen watched with a stopwatch.The magneto, a generator that provided spark to the engine, had previously been assembled by a single skilled worker who performed all thirty-five operations, and that worker averaged about twenty minutes per unit. After Sorensen's experiment, the twenty-nine men working in sequence finished each magneto in thirteen minutes and ten seconds.

Sorensen had proven something that no management theorist had articulated and no manufacturer had systematically applied: the line itself could think. Or rather, the line could replace thinking with rhythm, replace skill with subdivision, replace the craftsman's judgment with the engineer's measurement. A worker no longer needed to know how to build a magneto. He needed only to attach magnet number seven, sixteen times per hour, for ten hours per day.

Highland Park would transform manufacturing, warfare, consumer society, and the American worker's relationship to his own labor. It would also maim a generation of men who were paid extraordinarily well to lose their fingers.

A man must not be hurried in his work; he must have every second necessary, but not a single unnecessary second.

Henry Ford

The popular myth holds that Henry Ford invented the moving assembly line, but the truth is stranger and more instructive: he borrowed it from men who killed animals for a living. The Chicago stockyards had been moving carcasses on overhead trolleys since the 1870s, and Gustavus Swift and Philip Armour had discovered something profound about human behavior in the process. When you hang a dead steer on a moving chain, workers naturally synchronize their cuts to the chain's pace without anyone telling them to do so. The chain becomes the foreman.

Ford found the precision measurement revolution he needed in a Swedish immigrant named Carl Edvard Johansson, whose gauge blocks made it possible to measure to two-millionths of an inch. Ford purchased Johansson's entire company in 1923, making the Swedish metrologist's expertise a Ford proprietary asset.

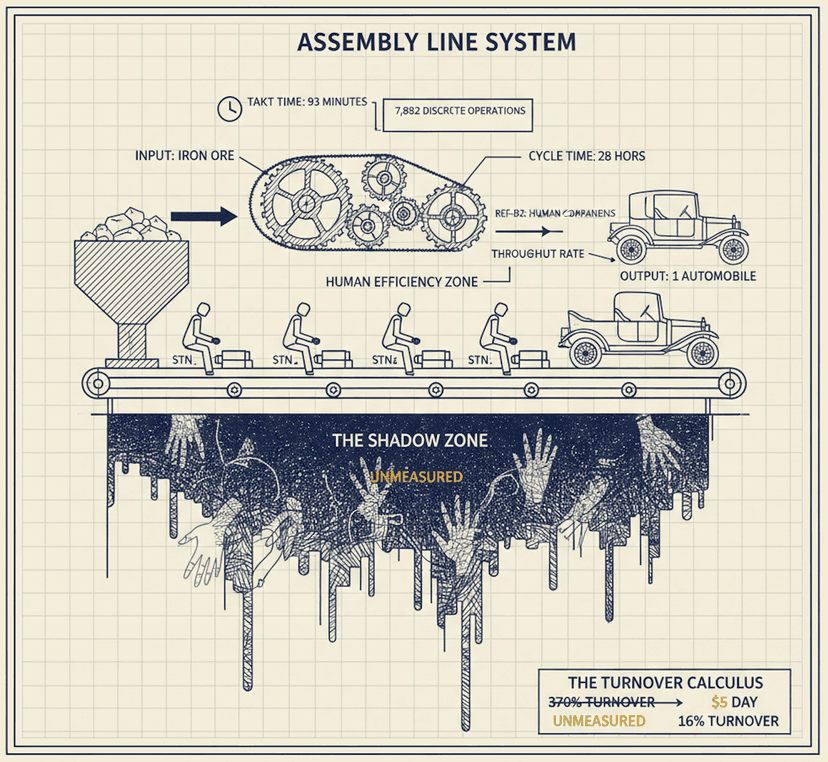

By October 1913, Ford's engineers had extended the magneto experiment to the entire chassis assembly. A car that previously took twelve hours and twenty-eight minutes to assemble now took five hours and fifty minutes. By January 1914, it took one hour and thirty-three minutes. Model T assembly was eventually divided into 7,882 distinct operations.

Clarence Avery, one of Ford's production engineers, calculated that the average worker at Highland Park walked 250 feet during an entire shift in 1914. Before the moving line, workers in automobile plants walked as much as four miles daily. Ford's real achievement was not speeding up human movement but rendering it almost unnecessary.

Between 1908 and 1916, Ford reduced the labor time for a Model T from 12.5 hours to 93 minutes. He cut the price from $850 to $360. Production rose from 10,000 cars per year to 730,000. By 1921, Ford Motor Company was producing more than half of all automobiles sold in America.

The moving line was also a maiming line. Highland Park in 1914 was extraordinarily dangerous. Fred Colvin, a journalist who toured the plant that year, reported that workers lost an average of sixteen fingers per month on punch presses alone. Metal shavings embedded in skin. Chemical burns from the paint shop. Hernias from lifting. Repetitive strain injuries that doctors didn't yet have names for.

Turnover was catastrophic. In 1913, Ford hired 52,000 workers to maintain a workforce of 13,000, representing a turnover rate of 370 percent. Men walked off the line mid-shift without a word, or they simply stopped showing up for the next day's work.

The assembly line's most important heir was also its most systematic critic. In 1950, a young Japanese engineer named Taiichi Ohno stood on the floor of a Toyota plant and asked a question that Ford's engineers had never considered: What if the worker could stop the line?

Toyota's Andon cord was a rope running the length of the assembly line that any worker could pull to halt production. Ford believed the worker was a component whose judgment couldn't be trusted. Toyota believed the worker was a sensor whose judgment was essential. Ford's line ran faster. Toyota's line ran better. By the 1980s, Toyota was building cars with a third of the defects and half the labor hours of comparable American plants.

II. The Materials

In 1905, at an automobile race outside Paris, Henry Ford witnessed a French car crash at high speed. Most spectators saw destruction. Ford saw opportunity. He walked onto the debris field and picked up a fragment of the wrecked vehicle, a piece of valve stem shaft that seemed impossibly light yet had survived an impact that had demolished the rest of the car.Ford later described turning the fragment over in his hands, testing its strength, marveling at its properties. "It was very light and very strong," he recalled. "I asked what it was made of. Nobody knew."

The fragment was vanadium steel, an alloy then used primarily in European racing cars and virtually unknown in American manufacturing. Ford's discovery of this material would become one of the most consequential accidents in automotive history.

Most American steel mills in 1906 could not achieve the temperatures required to properly alloy vanadium. Ford's solution demonstrated the vertical integration philosophy that would later make his plants legendary: if no supplier existed, he would create one. He sent for J. Kent Smith, an English metallurgical engineer, and funded a small foundry in Canton, Ohio to produce vanadium steel commercially.

C. Harold Wills, Ford's chief designer, immediately grasped the implications for weight reduction and crash survivability. Ford's metallurgists developed proprietary heat-treating methods that tailored vanadium's composition for specific applications: one formulation for axles that needed to absorb shock, another for gears that needed to resist wear, another for crankshafts that needed to survive rotational stress.

The Model T's front axle could be cold-twisted eight times without fracturing, a feat that Ford's salesmen demonstrated at county fairs. When salesmen performed the same test on competitors' axles, the parts snapped on the second or third twist. Audiences did not need to understand tensile strength to recognize that one car would survive the roads and the other would leave them stranded.

Consider paint: the Model T was famously available in "any color so long as it's black." The restriction was not mere inflexibility. Offering multiple colors would have required separate inventory, changeover costs, color-matching training, and scheduling complexity. Ford chose Japan black for durability and eliminated all this overhead.

When the Model T launched in 1908, it sold for $850. By 1925, systematic application of price-first discipline had reduced the price to $260, a decline of nearly 70 percent in nominal terms. A Ford worker could purchase a Model T with 52 working days of earnings, whereas the same purchase in 1908 would have required approximately 170 working days at prevailing wages.

Ford's price-first discipline found its most devoted heir in Ingvar Kamprad, the Swedish furniture dealer who founded IKEA. Kamprad called his approach "democratic design": good design should not be reserved for wealthy consumers. The flat pack transferred labor from factory to customer, eliminating assembly workers, reducing warehouse space, and cutting transportation costs.

III. The $5 Day

George Pullman is buried in a pit lined with concrete, surrounded by railroad ties reinforced with steel, covered by more concrete, and finally topped with an elaborate monument that conceals the fortress beneath. His family feared that workers he had employed would dig him up.Pullman, Illinois, was the first planned company town in American history. The Palace Car Company provided everything: housing, stores, a library, a church, parks landscaped with imported trees. Workers paid rent that returned their wages to their employer. When the Panic of 1893 collapsed demand, Pullman cut wages by twenty-eight percent without reducing rents. On May 11, 1894, nearly four thousand workers walked out. Eugene V. Debs organized a boycott. Rail traffic stopped in twenty-seven states. By late July, thirty-four strikers were dead.

The Pullman disaster offered a lesson: control workers' lives through ownership, and you trap them; trap them, and eventually they explode.

The chain system you have is a slave driver! My God! Mr. Ford. My husband has come home & thrown himself down & won't eat his supper... so done out!

Letter from a Ford worker's wife, January 23, 1914

By late 1913, Ford Motor Company's Highland Park plant had become the most productive industrial facility in human history and also one of the most difficult places in America to retain employees. The moving assembly line had reduced Model T assembly time from twelve and a half hours to ninety-three minutes. But the system also made the work miserable in ways that previous factory jobs had not been.

On New Year's Day 1914, Ford and his executives gathered to address the turnover crisis. James Couzens was present. Ford wrote the existing minimum pay of $2.34 on a blackboard and instructed his executives to figure out how much more the company could give. Every so often Ford walked in, said "Not enough," and walked out. Finally, someone snapped: "Why don't you make it $5 a day and bust the company right?"

On January 5, 1914, Couzens announced the $5 day. It more than doubled the prevailing wage. The Wall Street Journal condemned Ford for applying "Biblical or spiritual principles" where they did not belong.

But the $5 was not a wage increase. It was a profit-sharing arrangement: $2.34 in wages plus $2.66 in conditional payments. Ford created the Sociological Department, staffed with investigators who made unannounced visits to workers' homes. Did the worker rent or own? How much had he saved? Was the home clean? Was the diet adequate?

Workers who passed received the full $5. Workers who failed were placed on probation. The department also established the Ford English School, where immigrant workers graduated through a ceremony involving a giant prop cauldron labeled "The Melting Pot." They descended wearing native clothing and emerged wearing identical American suits.

One week after the announcement, ten thousand men surrounded Highland Park. By noon, fifteen thousand. Ford's security forces turned fire hoses on the crowd in January temperatures. But the men did not leave. They found dry clothes, or they did not, and came back. The wages were high enough that men would endure being attacked for the chance to earn them.

Ford's turnover rate collapsed from 370 percent to approximately 16 percent within months. The productivity gains from stable labor more than offset the increased wage costs.

Milton Hershey discovered that amenities without adequate wages produced the same instability. In 1937, when Hershey cut bonuses during the Depression, his workers struck. Farmers joined company loyalists to storm the factory and beat strikers with fists, clubs, and ice picks.

The company town never disappeared; it evolved. In May 2025, residents of Boca Chica, Texas, voted to incorporate as Starbase, headquarters of SpaceX. The vote was 212 to 6. Nearly all residents were SpaceX employees. The difference from Pullman is equity: SpaceX employees own shares in a company valued at over $200 billion.

Amazon's fulfillment centers track worker behavior through Time Off Task, logging any period when a worker is not actively scanning packages. The structure is Ford's: wages high enough to make the job attractive, surveillance comprehensive enough to ensure compliance.

IV. Vertical Integration

In December 1930, in a cafeteria carved from the Brazilian jungle, a worker stood and refused to line up for his food. The cafeteria had just switched to self-service, an American efficiency that required workers to queue with trays. "We are not dogs," he shouted, "that are going to be ordered by the company to eat in this way."The room exploded. Workers smashed dishes, overturned tables. They poured out of the cafeteria and attacked everything. Time clocks were torn from walls. Workers sank company vehicles in the Rio Tapajós while shouting "Brazil for Brazilians, murder all Americans!"

The company that built this cafeteria had also built the largest manufacturing complex in human history, where iron ore arrived by ship and emerged as finished automobiles twenty-eight hours later. The man who owned both believed the principles governing one should govern the other.

Fordlandia was Ford's rubber plantation in the Amazon, 2.5 million acres along the Rio Tapajós. Ford imposed American customs: a 9-to-5 schedule, mandatory American food, prohibition of alcohol, required attendance at square dances. After the 1930 riot and continued agricultural failures, Ford's grandson sold the properties for $244,200, a loss of approximately $20 million. Henry Ford never visited.

The River Rouge complex that Ford began building in 1915 would become Carnegie's logic made visible. The Rouge spread across two thousand acres, ninety-three buildings containing sixteen million square feet. At its peak, more than one hundred thousand workers punched in daily.

Albert Kahn designed the buildings as machines rather than containers. A journalist captured the promise: at eight o'clock, iron ore arrived from Ford mines. Twenty-eight hours later, the metal drove away as part of a finished automobile.

Having succeeded beyond imagination, Ford decided to extend the principle further. He would grow his own rubber. The rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis, originated in the Amazon but had been transplanted to Southeast Asia where it flourished. What Ford did not understand was South American leaf blight, a fungal disease endemic to the Amazon. The disease had evolved alongside the rubber tree for millions of years. In the Amazon, rubber trees grew scattered, rarely touching, which prevented the fungus from spreading. Ford's plantation packed trees together in neat rows. The fungus spread from tree to tree in waves.

Not one drop of latex from Fordlandia ever made it into a Ford car.

The distinction between Carnegie's success and Ford's failure was not integration itself but scope. Carnegie integrated activities he understood. Ford integrated an activity where his ignorance would prove catastrophic.

Seventy years later, Leonardo Del Vecchio would demonstrate both halves of this lesson. Born too poor to keep, placed in an orphanage at seven, Del Vecchio began manufacturing eyeglass frames in 1961 under the name Luxottica. By 2018, when Luxottica merged with Essilor, the combined entity controlled nearly everything in eyewear: manufacturing, retail, even vision insurance.

Ferrero, the chocolate company, broke its acquisition fast in 2014 by purchasing Turkey's largest hazelnut processor. But unlike Ford, Ferrero had spent decades learning the domain before integrating.

Delta Air Lines purchased an oil refinery in 2012, and industry analysts were skeptical. But Delta was solving a specific problem. The acquisition worked because Delta reconfigured the refinery for jet fuel, something an airline could master.

SpaceX manufactures approximately eighty-five percent of Falcon rocket components in-house. Raw materials enter Hawthorne; complete rockets emerge. But SpaceX integrates selectively, maintaining over three thousand suppliers for standardized components.

The lesson endures because the temptation endures. What distinguishes triumph from catastrophe is recognition: Do you understand what you are trying to control?

V. The Rigidity Trap

In December 1975, a twenty-four-year-old engineer named Steve Sasson walked into a conference room at Eastman Kodak carrying a device the size of a toaster. He had built it from scraps: a lens salvaged from a Super 8 camera, sixteen nickel cadmium batteries, several dozen circuits. The contraption took twenty-three seconds to capture a single image.Sasson pointed the device at the executives. When the image appeared, grainy and black-and-white, one hundred pixels by one hundred pixels, the men who ran the world's dominant photography company saw the future of their industry.

They asked how long before this matched film quality. Sasson calculated: fifteen to twenty years. They told him the technology was cute, but he should not tell anyone about it.

Kodak patented Sasson's invention and buried it. In 2012, Eastman Kodak filed for bankruptcy. Sasson received the National Medal of Technology from President Obama.

The executives were not stupid. By 1975, Kodak controlled roughly ninety percent of the American film market. They understood what digital photography meant for their model. If photographs existed as electronic files, there would be no film to sell. A technology that eliminated film was not an opportunity; it was a threat.

Clayton Christensen called this the "innovator's dilemma": the practices that make companies successful in established markets make them vulnerable to innovations that initially appear inferior.

In September 2000, Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph flew to Dallas to meet John Antioco, CEO of Blockbuster. Their company, Netflix, was losing money. Blockbuster had nine thousand stores, five billion dollars in revenue. Late fees generated over eight hundred million annually.

Hastings made his pitch: Blockbuster would acquire Netflix for fifty million dollars. Randolph watched Antioco's face. "I saw something new," he later wrote, "his earnest expression slightly unbalanced by a turning up at the corner of his mouth... John Antioco was struggling not to laugh."

Antioco declined. But four years later, Blockbuster launched its own online service. In 2005, Antioco eliminated late fees, accepting a loss of six hundred million dollars. Netflix's stock fell forty percent.

What killed Blockbuster was not blindness but captivity. The board, pressured by activist investor Carl Icahn, demanded immediate profitability. In 2007, they forced Antioco out. Three years later, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy. Netflix, which Blockbuster could have owned for fifty million dollars, is now worth more than two hundred billion.

When Steve Jobs announced the iPhone in January 2007, Nokia's internal presentation noted: "iPhone cannot be made." The assessment was technically correct. Apple's touchscreen required glass that did not exist, manufacturing processes that had not been developed. Nokia's analysts concluded that Apple would fail to deliver a working product.

What the presentation reveals is not incompetence but expertise. Nokia engineers were evaluating the iPhone against capabilities Nokia possessed. Apple was assembling capabilities Nokia did not know existed. Nokia's Symbian operating system was optimized for hardware that predated touchscreens.

In February 2011, Stephen Elop, Nokia's CEO, sent an internal memo comparing the company to a man standing on a burning oil platform: "We too are standing on a 'burning platform.'" Within four years, Nokia exited the mobile phone business entirely.

Is escape possible? IBM transitioned from mainframes to services. Amazon transformed from bookstore to cloud empire. Apple reinvented itself three times. Netflix disrupted Blockbuster, then disrupted itself by abandoning DVDs for streaming, then again by producing original content.

The survivors share characteristics. They are led by people who can see their companies from outside. They have cultures that reward bad news. They have ownership structures permitting long-term investment. And they have strategic humility: awareness that past practices may not bring future success.

The rigidity trap is not a failure of intelligence. It is a failure of identity. The question is not whether you can see the future but whether you can become someone else to meet it.